JACOBITES: LEGENDS OF THE ’45

16 Apr 2020

Charles Edward Stuart, portrait by John Pettie, 1892

A prince returning from exile to claim his rightful inheritance, rallying gallant clansmen to his standard: heady, immediate, unexpected victories and a final crushing defeat. A dream and a culture destroyed: a wound on the soul of a nation that remains unhealed to the present day

How much of this is true? And how much the cherished, burnished legend of the Jacobite rebellion of 1745?

It was all about the Stuarts, deposed from the thrones of Scotland and England and usurped by the House of Hanover.

It was all about Catholics and Protestants.

It was all about the Scots, particularly the Highlanders, hopelessly outnumbered, outgunned, outmanoeuvred, and decimated by a professional and unspeakably brutal Sassenach army.

It was all about passion and idealism and hope and yearning and high courage and unwavering loyalty to a royal fugitive with a price of £30,000 on his head, whom nobody ever thought of betraying to the sadistic English soldiers hunting him.

The truths of history are more complex, and much less convenient.

First of all, who was Charles Edward Louis John Casimir Sylvester Severino Maria Stuart, and what was his claim to the disputed throne?

It’s a long story. Suffice to say that Mary, Queen of Scots was Charles’s great, great, great grandmother, and he traced his lineage through Mary’s son James VI of Scotland. In 1603 the dying, childless Elizabeth I had designated James her heir, and thereafter James, already king of Scots, also reigned as James I of England, accomplishing what his mother had given her life for: the union of the crowns of Scotland and England.

Of the marriage of James I’s son Charles I to the French Catholic Henrietta Maria there were two sons, Charles II, who died without legitimate issue, and James, who with his first wife, the commoner Anne Hyde, converted to Roman Catholicism. Of James and Anne’s many children only two daughters survived to adulthood: Mary, born in 1662, and Anne, born in 1666. At the insistence of Charles II, a lifelong Protestant although he converted to Catholicism on his deathbed, both girls were raised as Protestants. Anne Hyde died in 1671, and James II married the fifteen year-old Roman Catholic princess of the Duchy of Modena, having reluctantly consented to the marriage of his daughter Mary to her Protestant cousin William III of Orange, who as stadtholder was the effective ruler of Holland.

James’s own reign, religion and political meddling were tolerated by an increasingly restive Parliament only as long as this second, indubitably Roman Catholic marriage produced no heir; but the birth of a son in 1688 ignited a conflagration and ‘glorious revolution’ that ended with the deposition of James II in favour of his Protestant daughter Mary and her husband William of Orange, and the deposed king’s flight to France with his wife Mary of Modena and his infant son James Francis Edward, the baby rumoured to have been smuggled into the royal birth chamber in a warming pan as a substitute for a stillborn royal child.

The exiled couple took up residence at Saint-Germain-en-Laye as guests of the sympathetic and ever opportunistic Louis XIV of France, who supported James and the endless machinations to restore him to the British throne which would come to be known as the ‘Jacobite’ cause (from the Latin Jacobus: James.)

Upon James’s death from a cerebral haemorrhage in 1701, the young James Francis Edward, with his mother Mary of Modena as his regent, was declared by his adherents James III of England and VIII of Scotland. And in the best Stuart tradition, after years of preliminary espionage, intrigue, and assurances of military and financial aid from France, young James launched three abortive attempts in 1708, 1715 and 1719 to wrest back power and proclaim himself king in Scotland. They failed, most notably and bloodily in 1715, and without the continued support of France the Jacobite cause could not succeed.

Charles as a child, portrait by William Mosman, circa 1750

The ‘uncrowned king of Scotland’ married Maria Clementina Sobieska, granddaughter of John III of Poland, on September 3, 1719, in Italy. The marriage produced two sons, Charles Edward, ‘the young pretender’, and Henry Benedict, who became a cardinal in the Roman Catholic church.

Charles Edward Louis John Casimir Sylvester Severino Maria Stuart was born in Rome on December 31, 1720, in a palazzo lent to James and Clementina by Pope Clement XI. He was a winsome, charismatic child, raised, like so many of the Stuarts, in a heady atmosphere of political intrigue, fluent in French and Italian and, as was later noted, speaking ‘the English or broad Scots very well’. Even as a small boy he was happy to pose for portraits in royal regalia or juvenile versions of military uniform, usually displaying the white rose which had become the symbol of the Jacobite cause. He believed very early in life that he had a mission, and when, in 1743, the disillusioned James proclaimed him Prince Regent, empowered to act in his name, Charles was certain of his destiny.

The white rose, a reference to James II’s former substantive title of Duke of York, had been appropriated by Jacobites as yet another covert means by which supporters of the cause identified themselves. Variously believed to be either the burnet rose (Rosa pimpinellifolia) dating back to before 1600, but single-flowered, or much more probably Rosa alba maxima, now called ‘the Jacobite rose’, it is a hardy shrub of great antiquity and longevity, thriving in adverse conditions (rather like the cause it represents). The full, dishevelled white blooms are heavily perfumed, and when cut the soft petals fall quickly. Any Jacobite who chose it as corsage, cockade or political statement would have found it fragile and ephemeral.

As for tartan, in which popular imagination sees entire clans identically dressed in tribal solidarity, it was neither reliably consistent in appearance nor uniquely Scottish. ‘Parti-coloured cloth’ had been woven and worn for three thousand years in central Asia and by Celts across Europe: the Romans recorded that these ferocious warriors wore cloaks ‘fastened at the shoulder… and striped or checked in design with the separate checks close together and in various colours.’

Anecdotal evidence of distinctive clan tartans in the 18th century is inconclusive, even contradictory, as are contemporary portraits. What we may consider a traditional Campbell tartan in one portrait can be an entirely different colour in another; and the variations inevitably resulting from local plants, dyes, patterns, weavers’ idiosyncrasies and the degree of weathering and aging of the garments, which were in any case intended as camouflage, produced a fabric far from uniform either in texture or design. Clansmen themselves were not always able to identify one another by the colours of their plaids, and even if the figures looming out of the mist on a dreich day in the Highlands were recognizable by tartan or badge, that did not guarantee them a warm reception, either during the ’45 or before it.

Jacobites, portrait by John Pettie, 1870

On the contrary. Beyond the Highland line lay another world, utterly alien in language and culture, a feudal society bound by fierce, hereditary loyalties and riven by ancient blood feuds. The clans who supported the Jacobite cause, and Charles Edward Stuart when he raised his standard at Glenfinnan on August 19, 1745, were not all Catholic; the clans whose allegiance remained with the Hanoverians were not all Protestant. Some chieftains came out openly for Charles, or sent their sons and tacksmen and tenants to him; some sent one son to the Prince and another to command loyalist militia; some, scarred by the failure of the rising of 1715, never declared their politics, and either did nothing and hoped the entire dangerous affair would blow over, or did nothing while making it possible for others close to them to follow their consciences. Many men, ordinary farmers, cottars, tenants of tacksmen, lairds or chieftains, did not go willingly but were coerced, threatened with fire and sword, and conscripted. Men deserted from the Jacobite army regularly, not out of disillusionment or fear but drifting away like shadows to return to their homes, their families, their crops. Sometimes they went back to Charles. Often, with prescience, they foresaw their deaths, buried their weapons if they had any, and waited, praying that the storm would pass.

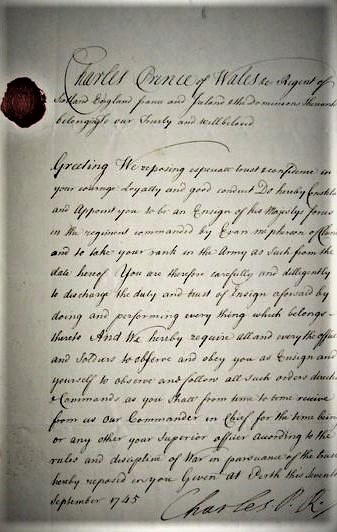

Jacobite commission, signed by Charles Edward Stuart

It ended eventually, after an almost unimaginably bitter winter throughout which troops, horses, supply wagons and heavy ordnance had manoeuvred across some of the roughest terrain in Britain, through waist-deep snow and icy rain, over mountain passes, drovers’ tracks, and the garbage-strewn cobbled streets of hostile towns, living off the land, feeding off the fear, contempt and derision of the local populace, each area according to its politics. It is no wonder that when these two armies faced one another in the sleet on Wednesday, April 16, 1746 on Drummossie Moor (Scottish Gaelic Blàr Chùil Lodair: Culloden), it was with a savage hatred born of months of privation and frustration. No quarter was given or expected by either side.

The Jacobite army on that April morning was not entirely Scottish. As well as Gaelic-speaking clansmen, there were Lowland Scots, many conscripted; volunteers; deserters from the Scottish militia regiments of the British army or enlisted from among the prisoners after Charles’s victory at Prestonpans. Two infantry battalions and a squadron of cavalry were French, as well as artillerymen, engineers and volunteers: these were the ‘Wild Geese’, the Irish Brigade of the French army, and the Royal Écossais, a Scottish unit of the French army raised in 1744.

On the other side of the moor, with the sleet beating on their backs, the British army waited for the opening fire, memories of defeat and humiliation and the stripping and plundering of their dead by the enemy at Prestonpans and Falkirk foremost in their minds. Many of these men were English, many Scots or Anglo-Irish: the 1st, 21st and 25th Foot were Scots regiments, as were the Gaelic-speaking Argyllshire Militia, the Duke of Kingston’s Light Horse, and the regulars of Loudon’s 64th Highlanders. Many soldiers wore Highland dress, and there were many for whom the ranting slogans and skirling pipes of the rebels were echoes of a culture shared.

It ended, as wars end, in a welter of blood and slaughter. No British regiment ever bore Culloden among its battle honours, and its name remains a byword for infamy.

And, in the haunting tragedy of the aftermath, legends were born.

Charles took to the heather for many weeks, with the staggering sum of £30,000 on his head and vigorously pursued across the Highlands and islands by, among others, two of the most notorious perpetrators of atrocities in the course of the ‘pacification’: Captain Caroline Scott of the British army and Captain John Ferguson, Royal Navy. Both were Scots.

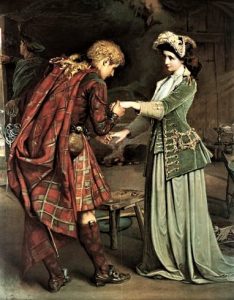

The fugitive prince and Flora MacDonald, portrait by William Joy, 1891

Finally Charles was brought to bay in South Uist, and all seemed lost until a new heroine emerged in the person of Flora MacDonald, stepdaughter of ‘One-Eyed Hugh’ MacDonald, who is credited with organizing Charles’s escape with Flora by boat ‘over the sea to Skye’. On paper this escapade seems just another exercise in futility and disorganization, typical of the ’45, as it was necessary for Charles to leave Skye and skulk again for several weeks on the mainland until, on September 20th, he boarded a French warship which had entered Loch nan Uamh. He reached Britanny nine days later.

It was claimed that no one ever considered betraying the prince, although Flora freely confessed, offering a tissue of lies and half-truths that incriminated many islanders when she was arrested. Remarkably, after several months of increasing celebrity as a political prisoner in London, she was pardoned in the general amnesty of 1747, married her kinsman Allan MacDonald of Kingsburgh on November 6th, 1750, and left Skye with him in 1774 for North Carolina, one of thousands of emigrants who, decades before the Highland Clearances, conceded to chronic poverty and disease, and the relentlessly hostile climate that engendered crop failure and famine.

The American revolution destroyed any hope of peace or refuge from political turbulence, and Allan MacDonald, who had commanded loyalist militia in 1745, accepted a commission in a battalion of the newly formed Royal Highland Emigrants and gave his allegiance to George III. He suffered grievously for his loyalty as a prisoner of war of the Americans before he was released on parole eighteen months later and left to walk to New York to negotiate his own exchange. Flora, meanwhile, alone with her youngest son on a hundred-acre plantation, faced her own dangers. She described it, characteristically in the third person, thirteen years later.

Mrs. Flora MacDonald, being all this time in misery and sickness at home, being informed that her husband and friends were all killed or taken, contracted a severe fever, and was deeply oppressed with stragling partys of plunderers from their army and night robbers, who more than once threatened her life wanting a confession where her husbands money was. Her servants deserting her, and such as stayed grew so very insolent that they were of no service or help to her.

Flora MacDonald, portrait by Allan Ramsay, circa 1749

She lost books, treasures brought from Skye and silverware, and was finally forced to flee. She was reunited with Allan in New York. Two and a half years had passed since they had seen one another.

Allan was posted to Nova Scotia where, Flora wrote, We continued all winter and spring, covered with frost & snow, and almost starved with cold to death, it being one of the worst winters ever seen there. Ill, homesick and suffering from arthritis in two previously broken arms, she returned to Skye in the spring of 1780. She died on March 4th, 1790, preceded by Charles Edward Stuart, who had died in Rome in January of 1788, an alcoholic depressive with whom conversation on the subject of his failed rebellion was forbidden because it threw him into such depths of melancholy. He had never returned to the country to which he had brought such misery and disaster.

George IV, portrait by David Wilkie, 1829

But the rose-ringed legend lingered, burnished by time, and given new life by the publication in 1814 of Sir Walter Scott’s Jacobite novel Waverley. The rehabilitation of the Highlands had begun. It reached new heights when George IV visited Edinburgh in 1822 and wore at a levée at Holyrood to celebrate his birthday a variation of Highland dress that was both incongruous and magnificent; and its apogee in 1842 with the first visit to Scotland by a royal fan of Scott’s novels, Queen Victoria, and her consort Albert. The love affair between the House of Hanover and the Highlands endures even to this day.

It seems no coincidence that before Scott’s wildly popular novels were published the word Sassenach was almost unknown. Deriving from the Scottish Gaelic Sasunnach, the Irish Gaelic Sasanach, the Latin Saxonēs, and the Old English Seaxon, it means ‘Saxon’, and is derogatory. Its recorded use, according to the Collins English Dictionary, was almost nil before 1801, peaked in 1842, and again dwindled almost to non-existence by 2006.

As the Scots dispersed to North America, China, Australia and New Zealand, driven from their homeland by the death blow to a moribund clan system which had been delivered at Culloden, they carried with them grief, bitterness, anguish and nostalgia; and from this potent combination arises legend. But the truth is more compelling. It is the truth that chills the blood and stirs the soul. It is the truth that Coronach tells.