O CAPTAIN, MY CAPTAIN

15 Oct 2019

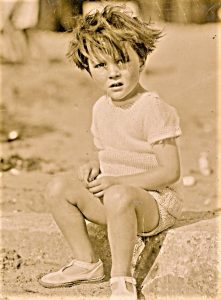

young Douglas at Ramsgate

The youngest son of Ada Lilian Reeman (née Waters) and Charles Percival Reeman was born on October 15, 1924 in Thames Ditton, Surrey. He was named Douglas after Field Marshal Douglas Haig, who had commanded the British Expeditionary Force on the Western Front during the Great War, in which Percy had served, and Edward for Lilian’s father Ted Waters, a former colour-sergeant in the 31st Huntingdonshire Regiment, and a well-known and popular resident of the nearby town of Esher.

It was Ted Waters who took his grandson to see H.M.S. Victory in Portsmouth, when the three Reeman boys and Lilian returned to England from Singapore, where Percy, a Royal Engineer, had been seconded to a Gurkha regiment. “That was when it hit me,” Douglas recalled years later. “Aboard the troopship, the engines starting, things vibrating on the table, the soldiers, my mother saying don’t talk to them. Afraid we’d pick up too much bad language, I suppose. But it was magic… the ship and the sea, and Singapore at the end of it.”

And he did talk to them. To everybody. The soldiers, the seamen, the Gurkhas, the Chinese amah in steamy, exotic Singapore, and he came home dazzled and dreaming. And visited Victory and went to Navy Week, and the sea and the ships and the Royal Navy claimed him and never let him go.

Percy, Sandown Park 1914

In September 1939, for the second time in the twentieth century, Britain declared war on Germany. The Guv’nor, as his sons called him, was once more in uniform, taking a train every morning from Esher to the War Office in London. Lilian worked down the A3 highway on the outskirts of the village of Cobham at Fairmile Marine, which produced for the Admiralty the eponymous fast and heavily armed Fairmile motor torpedo boats in which her youngest son would serve. Jonathan, five years older than Douglas and a peacetime naval reservist, was the first to leave on active service. Peter, the middle son, joined the Royal Air Force. War took both their lives, Jonathan dying aboard H.M.S. Barham in the Mediterranean in November of 1941, Peter, returning from the Far East and unable to find peace in a post-war world, committing suicide some years later.

Lilian, left, with friends

Douglas, not yet twenty-one when the war ended and desperate to remain in the Royal Navy, spent six months in Kiel working with the German navy before coming home to join the Metropolitan Police and walk the beat in London’s East End, as a uniformed constable and then a plainclothes detective. It was a shabby, grimy, gritty world of rackets and rationing, where tough young criminals, recently demobbed and not infrequently armed with smuggled service revolvers, recognized in the medal ribbons on the tunics of equally tough, newly recruited young coppers men who had fought in the same theatres of war. And in the grim, bombed streets, the illegal betting shops, at the dog tracks and street markets and in the raucous pubs on a Saturday night, Douglas talked to people. And they told him their stories as, later, he would tell the world.

Peter

In 1958 he published his first novel, A Prayer for the Ship, an evocation of “his war” in motor torpedo boats. Other books followed, in the course of a career now successful enough for him to turn his attention to the insistent presence in his mind of an eighteenth century naval officer, a solitary, sensitive, compassionate man, a contemporary of Douglas’s hero, Horatio Nelson.

Jono, Scapa Flow, 1941

To his American publisher, Walter J. Minton, Douglas mooted the idea of a novel about this man and his life and times in the golden age of fighting sail. Minton was enthusiastic. “What are we going to call this guy?” he asked, and Douglas, recalling the name of the rather fierce army officer, a Cornishman, who had helpfully taken the lines of Douglas’s motor yacht Guardian on a fast-falling tide in the Jersey port of Gorey, said, “Bolitho. Captain Richard Bolitho.”

The Bolitho novels brought him fame and the friendship of people all over the world. Men, women, and the children to whose dreams and zest for adventure Douglas himself was always sensitive: he wrote the midshipman trilogy especially for younger readers. He was loved by every one. Sailors considered him one of their own; strangers would come up shyly at book signings and events and find themselves engaged in deep conversation with an unassuming man who, with humour and often with compassion, encouraged them to tell their stories.

They gave him their hearts. As I gave him mine.

My love, my dearest of men, for everything you were and are, and everything you freely gave, your love, your spirit, your gentleness, your courage, your faith, your cherished companionship throughout the years we shared, I salute you.

Douglas, front row, second from left, and brother officers in immediate post-war Germany, 1945