SOME ENCHANTED EVENING

5 Oct 2019

Some enchanted evening, you may see a stranger,

You may hear his laughter across a crowded room,

And somehow you know, you know even then,

That somewhere you’ll see him again.

RICHARD RODGERS, “SOUTH PACIFIC”

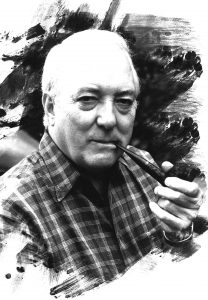

It couldn’t happen. I was, and am, a cynic and a feminist, and I didn’t believe in love at first sight. He was married and famous and twenty-nine years older than me, and although his marriage had become difficult no one knew, and he was an honourable man. I was an honourable woman. And when the evening and his book tour of Canada ended, three thousand miles of cold Atlantic lay between us.

It couldn’t have happened. But it did.

This is how we fell in love.

One Saturday morning in 1977, as an aspiring young novelist, I went to my local library in the suburb of Toronto where I grew up and took a battered paperback off the revolving rack. Its title was Signal— Close Action! and I read the blurb and said to myself, “I wonder if this guy really knows how to write about the eighteenth century.”

I checked the book out. I read it. He did. I was hooked.

Fast forward to May of 1980, when I was a blurb-writing proofreader at a Toronto publishing house and saw a copy of the weekly trade publication, The Bookseller, on the glass-topped table in the art director’s office. There was another magazine half obscuring the cover photo, but I thought, I know those eyes, and uncovered it, and, sure enough, they were the distinctive, dark grey, deep-set eyes of the man who had become, with Winston Graham, my favourite English gentleman novelist. Alexander Kent, whose real name was Douglas Reeman, was coming to Toronto in the course of a cross-Canada tour to promote his new novel A Ship Must Die, and was scheduled to appear at the lakeside cultural centre, Harbourfront, on the evening of June 6th.

I fought my natural shyness and went. It was a wild, stormy Friday night (typical D-Day weather, he would call it) and he had spent the day doing radio and TV interviews. He read the first chapter of A Ship Must Die (and he hated reading in public, although he would very happily read each day’s work to me, doing all the accents) over the sound of rain pounding on the roof of the aptly named Brigantine Room.

And then he finished, and the publisher’s PR man asked for questions from the audience.

And then he finished, and the publisher’s PR man asked for questions from the audience.

Dead silence.

I thought, it’s now or never, and stood up. The Englishman looked at me kindly from the stage, over his reading glasses, and I said into the silence, “At the end of The Flag Captain, Richard Bolitho is very obviously romantically involved with Catherine Pareja. And then in the next book there’s no sign of her. WHATEVER HAPPENED TO CATHERINE PAREJA?”

Pause. Then he said in that beautiful voice of his, “I don’t know. I haven’t written the book that goes between those two yet.”

There were a couple of questions from other people, and then it was all ending and he came down from the stage and was standing chatting to some one like an ordinary human being, and my father, who had driven my mother, by now also a Kent fan, and me downtown in the rain to this event, said to me, “You’ve come all this way. Why don’t you just go and say hello to the guy and tell him how much you enjoy his books?”

Oh, my God, no, I thought, overcome. And then the next thing I knew… there was my dad talking to the great man as if they’d been friends for years, and my dad turned to me and said the fateful words:

“And this is my daughter….”

Fate touched us both that night. Douglas looked at me, and I looked at Douglas. And something in my soul leaped in recognition, and I felt I had known this man and been waiting for him all my life. And later… years later… he told me he had felt the same.

We spoke for twenty minutes. I told him a joke about Nelson and he bellowed with laughter. He thought I was an actress. I told him I was a writer. He invited me to “write to the publisher. No… write to me,” and gave me his address, the address of this beloved house where I still live. He couldn’t write it himself because he had gout in his right hand, “a fine thing for a writer on tour,” he said, but he pulled a paper Bolitho bookmark from the copy of A Ship Must Die under his arm (which was in a sling) and gave it to me with his teeth, and I scribbled the address on it. The bookmark still bears the imprint of his teeth.

We wrote to one another for four years. In April of 1983 his wife died, and he went into a tailspin of grief and depression. My hand across the Atlantic sustained him, and the tone of our letters changed. I had known I was in love with him for many months; but I also knew it was impossible, and that I could never tell him. Now something greater than ourselves decided that, against these impossible odds, we would be together.

On the evening of July 9th, 1984, he walked across the lobby of the old and elegant Royal York Hotel in Toronto where my English grandmother had once been a chambermaid, and opened his arms to me. I took him to dinner at Fenton’s, a favourite restaurant, now gone, where we sat in a courtyard under trees threaded with starry lights. He asked me to marry him.

It was a wild leap of faith for him, because he had been, and could be, deeply hurt. For me it was commitment of a magnitude I had never contemplated, but if I had been too afraid to accept the great gift of his love I would have spent the rest of my life regretting it.

On October 5th, 1985 we were married in St. James’s Cathedral under the faded ensigns and battle honours of old Canadian regiments, in the presence of our families, and many friends who had come from all over the world to witness the joining of our hearts and spirits.

… And one night not long after we were married we did return to Fenton’s and sit under the star-hung trees and discuss “whatever happened to Catherine Pareja”. Eventually he wrote Honour This Day for me, and inscribed my copy: To my darling Kim, the girl who asked the question on June 6th, 1980. That question and so many more are now answered.

And we lived happily ever after, until the end. There is always an end, and the price of great love is great pain. But the lovers’ story shines in memory, and lives on, and becomes immortal.