WOLFE: THE PATH, THE GLORY

2 Jan 2020

Canada est un pays couvert de neiges et de glaces huit mois de l’année, habité par des barbares, des ours et des castors…. Quelques arpents de neige.

VOLTAIRE (FRANÇOIS-MARIE AROUET), 1758

Major-General James Wolfe, 1759

There was no snow on this September morning, only a vast, living silence under the stars: the concerted creak and dip of oars, the uneasy shuffle of boots on bottom boards, a muffled cough as men, packed closely together, gripped their weapons, stared into the blackness and listened, waiting for whatever would come. The night was calm, the current strong: the tide, in this river of seven hundred miles, ebbing rapidly. From the unseen shore, after the heat of the day, a cool wind brought the scent of the pines.

The quarter moon had risen at 10 p.m., laying a faint, camouflaging track on the water to confuse the eye, and the boats slipped through the shadows. They had begun to embark at about 9 p.m., the light infantry and the Royal Americans first, followed by the other regiments in order of seniority, dropping away from the Sutherland at midnight at the hoisting of the signal: two lanterns, one above the other, in her maintopmast shrouds. At 1:35 a.m. the tide began to flow, and at 2 the signal to proceed was given. The commander-in-chief, in Sutherland’s barge, took the lead.

He sat on the thwart, his six-foot frame uncomfortably cramped, maintaining the silence he had ordered all men to observe in the boats, with a fusil slung across his back, a cartridge pouch with seventy rounds of ammunition suspended from his belt, and a bayonet at his left hip. Recent, debilitating illness had drained him, physically and spiritually, and he was haunted by the possibility of failure. He had seen the fates of generals and admirals arraigned for dereliction of duty: court-martial, professional oblivion, dishonour, or worse. He had held his first commission at the age of fourteen: he was now thirty-two, and half his life, spent in continuous service, had been merely the prelude to this rendezvous with destiny.

He focused his mind on a stanza of Gray’s Elegy, a copy of which his fiancée had given him before he had left Portsmouth, and which he had annotated the previous evening in his cabin aboard Sutherland.

The boast of heraldry, the pomp of power,

And all that beauty, all that wealth e’er gave,

Await alike th’ inevitable hour.

The paths of glory lead but to the grave.

The barge nudged into the shallows, and, adrenaline coursing through his blood, he was up, into the water, splashing ashore. The inevitable hour had come.

***

Time had matched him with this hour: time and a crucible of war, which had taken an affectionate child in an ensign’s uniform writing letters to his “dearest Mamma” and by its alchemy produced a man, impetuous, hot-tempered, over-sensitive, disciplined, meticulous, and intolerant. Devoted to his family and friends, he had a capacity for love that would never be truly fulfilled, and an intense vulnerability: he never forgot a kindness, and very seldom forgave an injury. Trust once lost was never given by him again, a quality he recognized in himself, writing in a moment of excoriating self-analysis, “I have that cursed disposition of mind, that when once I know people have entertained a very ill opinion, I imagine they never change. From whence one passes easily to an indifference about them, and then to dislike…. There lurks a hidden poison in the heart that is difficult to root out.”

the young Wolfe, portrait attributed to Joseph Highmore

Aware of his own military genius, he had felt for most of his life ignored, undervalued, denigrated, and often openly insulted by subordinates and superiors alike. Initially shy with women, although he gained grace and confidence, he remained conscious of his own singular physical characteristics: he was six feet three inches tall and very thin, with flame-red hair, long, nervous, restless fingers, pale skin that blushed furiously with any access of emotion, and his mother’s unfortunate profile, which would be so cruelly lampooned at Quebec and immortalized in a host of bad portraits and tasteless souvenirs at the apogee of his posthumous fame. Only the painting attributed to Joseph Highmore was considered a good likeness by his family until George Townshend, one of Wolfe’s trio of combatative brigadiers at Quebec, produced from life, without a trace of his signature malice, the iconic and endearing watercolour of his mercurial commander that captures the elusive qualities of his face: the piercing, heavily lidded blue eyes, the patient, somewhat quizzical expression, the cleft chin, and an essential gentleness about the mouth, a gentleness for which, in life, Wolfe was known, and in death remembered.

Time. There had never been enough time: enough peace, enough warmth, enough comfort, enough nourishment, enough freedom from physical and mental stress. No time to study, to travel, to observe, to discover, as a shy and awkward lover, the mysteries and delicacies of lovemaking; no time to marry, to father the children he longed for, to walk, as he once wrote wistfully to his own father, in his garden and sample his own sun-warmed figs. There had only been war.

And now, at the foot of these cliffs, time stopped. Two hundred and fifty feet above, men were climbing, cursing, dislodging soil and stones, hauling weapons: those who had reached the top and dispatched the French sentries were silhouetted against the stars. The path, the metaphor for his life, awaited.

He drank briefly from an offered flask: water, not alcohol. He seldom drank spirits, although he had ordered an issue of rum for the men tonight, knowing it would hearten them. Chronic dehydration had led to infections of the bladder and urethra which had felled him repeatedly, with fever and bloody urine and excruciating pain, most recently in the previous week, and he was still desperately ill, despite his efforts to conceal it.

He began to climb.

***

James Wolfe was born on January 2, 1727, at Westerham, Kent, the first surviving child of Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Wolfe, a career soldier of Irish descent who had served with Marlborough, and his much younger wife Henrietta Thompson Wolfe, an imperious beauty who claimed descent through her Yorkshire family, the Tindals of Brotherton, from Edward III and Shakespeare’s ‘Hotspur’, Henry Percy. Throughout his life James’s relations with his English and Irish relatives, particularly his uncle Major Walter Wolfe, who had retired to Dublin, and his cousins, the Goldsmiths of Limerick, remained fond and close.

Almost exactly a year after James’s birth a paler, frailer sibling arrived, and was christened Edward after his father. Where Jemmy led, Ned would follow, even through waist-deep snow in the brutal winter of 1743 as a fifteen year-old ensign in Colonel Scipio Duroure’s 12th Regiment of Foot, sharing a horse with the sixteen year-old James, also an ensign but already discharging the duties of adjutant. After a particularly onerous march James wrote to his father from Aschaffenburg, near Frankfurt: “The men almost starved. They nor their officers had little more than bread and water to live on, and that very scarce. The King is in a little palace in such a town as I believe he never lived in before. It was ruined by the Hanoverians, and everything almost that was in it was carried off by them some time before he came. They and our men now live by marauding…. The French are burning all the villages on the other side of the Mayne, and we ravaging the country on this side.” And, as the army was as much a family as the Royal Navy, and friends and former brothers-in-arms kept in as close touch as was possible, he added: “Brigadier Huske inquires often if I have heard from you lately, and desires his compliments to you. He is extremely kind to me, and I am most obliged to him. He has desired his brigade-major Mr. Blakeney, who is a very good man, to instruct me all he can. My brother intends writing very soon. We both join in love and duty to you and my mother.”

Meanwhile, Ned was reporting busily: “They say there are many wolves and wild boars in the woods; but I never saw any yet, neither do I desire.”

There was something far more lethal in the woods, dogging the footsteps of the allied forces of Britain, Hanover and Austria under the personal command of George II: a French army of 70,000 commanded by the Duc de Noailles, one of the most formidable soldiers of his time. Inexplicably, Noailles ceded command of a large contingent of infantry, artillery and cavalry to his less capable nephew, the Duc de Grammont, who abandoned an unassailable position to attack the allies on open ground near the village of Dettingen, in what is now Bavaria, on June 27th, 1743. The Wolfe boys, receiving this baptism of fire, saw the mathematical precision of drill disintegrate into the chaos of hand-to-hand fighting: Duroure’s, in the front line, suffered the highest casualties of any allied regiment engaged that day. The colonel’s horse was shot from under him, as was James Wolfe’s; the King was thrown, and led the Hanoverians on foot; his son William, Duke of Cumberland, who would figure prominently in James’s life, took a musket ball through the calf, and Wolfe wrote in a graphic dispatch to his father after being, with Ned, under artillery fire for nearly three hours and then in close action for more than two: “I sometimes thought I had lost poor Ned, when I saw arms, legs, and heads beat off close by him. He is called ‘the Old Soldier’ now, and very deservedly.”

Dettingen, with 750 British, Hanoverians and Austrians killed and 1,600 wounded, and between 2,000 and 4,000 French dead, was considered a victory. A British cavalryman, writing home of the “dead and mangled bodies, limbs, wounded men” and terribly injured horses he saw on the battlefield in the rain the following morning, revealed that “this sight shocked my very soul.”

The armies regrouped, reinforced, and did not engage again that year.

On June 3rd, 1744, James was promoted to captain in the 4th Regiment of Foot, the King’s Own, also known as Barrell’s after its nominal colonel, Lieutenant-General John Barrell: its lieutenant-colonel in the field was Robert Rich, who welcomed the newly blooded young captain and would become a friend and champion. Ned, now a lieutenant, remained with the 12th. The brothers saw each other occasionally and corresponded as regularly as circumstances permitted, but a letter from the 12th’s surgeon expressing concern over Ned’s health never reached James, and he was in winter quarters in Ghent and unaware of the gravity of the situation when Ned died in October, probably of tuberculosis. He wrote to his parents on the 29th of that month, overcome with grief and self-recrimination.

“It gives me many uneasy hours when I reflect on the possibility there was of my being with him some time before he died. There was no part of his life that makes him dearer to me than that which you have often mentioned— he pined after me…. He lived and died as a son of you two should, which, I think, is saying all I can.”

In May of 1745, at Fontenoy, Ned’s old regiment engaged once more in bloody combat with the French. James, who was kept in reserve with the 4th and never ordered out of Ghent, wrote to his father after the allies’ ignominious defeat that Duroure’s “has suffered very much, 18 officers and 300 men killed and wounded. I believe this account will shock you not a little, but ’tis surprising the number of officers of lower rank that are gone.”

Not for the first time, he contemplated the ephemerality of life, and a future in which the only certainty was death. He was young but no longer youthful: his had become an older, darker soul, prone to depression, and driven by ambition and an awareness of the passing of time.

On the 22cd of June, 1745, general orders announced his appointment as “Brigade-Major to Pulteney’s Brigade.” He was eighteen years old.

***

The cliffs had been thought unscalable, except by Wolfe himself. The French had not, apparently, thought suspicious the spectacle of four senior British officers staring at the Anse au Foulon through telescopes from a vantage point on the opposite bank, when he had been explaining, yet again and more testily, what the other three seemed unwilling or unable to understand. After a summer of feints and manoeuvres and skirmishes and infuriatingly unsuccessful forays, perhaps Montcalm had dismissed the episode of the telescopes as merely another caprice on the part of the British. Deserters, in a traffic that flowed both ways across the St. Lawrence, had reported his response.

“We need not suppose the enemy has wings.”

He had placed his trust in the river and the country, and what time would do to both. These impudent invaders would be forced to withdraw soon, or be locked in by the Canadian winter.

The heat was still intense in the afternoons, but the quality of the light had changed. Time, in the turning of a leaf, in the coolness before dawn… time in the flood of the river, the flood of years. Time was running out.

The stars were veiled with cloud now, and rain intensified the fragrance of the pines.

***

regimental colours of Barrell’s, the King’s Own, at Culloden, 1746

Culloden cast its long shadow over the rest of Wolfe’s life, although, as aide-de-camp to the foul-mouthed old cavalryman Lieutenant-General Henry ‘Hangman’ Hawley, he was not fighting with his regiment, Barrell’s, the King’s Own, on the morning of April 16, 1746. He remained on the right of the line with Cobham’s Dragoons and Kingston’s Light Horse, which Hawley did not order into action until the entire right wing of the rebel army had thrown itself on Barrell’s. He did not see, except at a distance and through the smoke, Barrell’s break under the impact of the charge by the Stewarts of Appin and Atholl and the Camerons under Lochiel, and throw it back with bent and bloodied bayonets; did not see his friend Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Rich, fighting with inhuman courage beside the colours, receive six head wounds; did not see Rich’s left hand struck from his wrist and his right forearm almost severed by a Highland broadsword; did not see until afterwards Lord Robert Kerr, son of the Marquess of Lothian and captain of Barrell’s grenadiers, dead on the ground with his skull split from crown to collarbone. He did not, in all probability, feature in the apocryphal story that sometimes had the Duke of Cumberland, sometimes, more characteristically, Hawley, pointing to a wounded Jacobite, identified as Charles Fraser of Inverallochy, and saying, “Wolfe, shoot me that rebel dog,” whereupon the indignant young major retorted, “My commission is at Your Highness’s disposal, but I can never consent to become an executioner.” Wolfe loathed insubordination and would certainly not offer it to his commander-in-chief, and it is highly unlikely, despite his personal hatred of Hawley, that he would have behaved with insolence toward him. He remained on good terms with Cumberland, and was more than once recommended for promotion by him, until the Duke’s spectacular fall from grace following his surrender of Hanover in 1757.

But for Wolfe the dark memories remained, and an appreciation of the raw courage of the Scots. He had seen that ferocity unleashed. He could not know that within thirteen years, on a sunswept plateau on a September morning, it would be his to command.

***

Although preliminary peace talks between Britain and France had begun in the summer of 1746, the bloody and protracted War of the Austrian Succession ground to a halt only with the ratification of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in October of 1748. Its terms merely restored the status quo, and sowed the seeds of another war.

Elizabeth Lawson

By then Wolfe had spent several years in garrisons in Scotland, escaping the punishing climate and hostile inhabitants only briefly for a return to conventional soldiering in the Low Countries, and to London on leave in the winter of 1746. And there, hardened veteran of several campaigns, he surrendered his heart and fell “hopelessly in love”. Those who had thought him disinterested in women, or only a brain fixated on promotion in a passionless body, or a repressed homosexual, although nothing in his relationships or letters suggested this, were stunned by its effect on him.

She was Elizabeth Lawson, maid of honour to the Princess of Wales and niece of Wolfe’s old mentor, Lieutenant-General Sir John Mordaunt. They were reunited when, now lieutenant-colonel of the 20th Regiment of Foot and gaunt from the scurvy and malnutrition of too many cold years in the Highlands, he was at last granted, not the foreign leave he had requested to repair what he saw as the deficiencies in his education by studying engineering and artillery tactics at the military academy in Metz, but six months in London.

He was still in the throes of what his mother called his “senseless passion” and in no mood for opposition, although his parents were, as he wrote to his close friend, Colonel William Rickson, “somewhat against it.” The pressure from his mother was unrelenting, he told Rickson: she thought he could do better than Elizabeth Lawson and her £12,000 and had her eye “upon one with £30,000.”

He arrived at his parents’ house in Old Burlington Street and immediately found himself embroiled in psychological warfare. Elizabeth, who obsessed him, had obviously cooled toward him and was entertaining other suitors; the Croydon heiress, his mother told him, was still available with her £30,000; and was James aware that Lady Lawson, Elizabeth’s mother, had been a loose woman before her marriage, and it was possible that her daughter was the same?

Henrietta Wolfe had gone too far. She had occasionally, in her letters, reproached her son for his temper: he had frequently apologized for it and attempted to control it. But something vital in James Wolfe snapped that day and he turned its full fury on her, and then stalked out of the house and took lodgings in a nearby street, where, to the fascination of the neighbours, he relieved his emotional and sexual frustrations in the longest and most uncharacteristic debauch of his life. Rumour had it that he had arrived drunk at a ball and loudly proclaimed his love for Elizabeth Lawson, and threatened to horsewhip a rival: whatever indiscretions he committed, Elizabeth warmed no more to this new, rakehell incarnation than to the staid James Wolfe she knew. She ended the relationship. Shattered, he lost himself in alcohol, emerging briefly to listen from the public gallery to debates in the House of Commons on the future of British North America, until his outraged body rebelled and he became ill. His mother continued her campaign. He wrote to her in anguish, “How could you tell me you liked her, and at the same time say her illness prevents her wedding? I don’t think you believe she ever touched me at all, or you could never speak of her ill-health and marriage, the only things in relation to that lady that could give me the least uneasiness.”

He wrote to his father with a certain battered dignity, “You called my situation ridiculous, and indeed it was,” and apologized for what he said had been done “out of passion and anger, when I had the honour to be near you.” To his friend Rickson he confessed, “In that time I committed more imprudent acts than in all my life before. I lived in the idlest, most dissolute, abandoned manner that could be conceived, and not out of vice, which is the most extraordinary part of it. I have escaped at length, and am once again master of my reason, and hereafter it shall rule my conduct, at least I hope so.”

He never recovered. Four years later, her portrait in Sir John Mordaunt’s dining room still disconcerted him so much that he could barely eat, and any mention of her name affected him profoundly.

He took his wounded heart to Paris. The Croydon heiress unexpectedly bestowed her £30,000 on one of his boyhood friends in February of 1751. Elizabeth Lawson died, unmarried, some weeks before he sailed for Quebec.

***

For a few brief months, in this interlude of peace under the auspices of the Earl of Albemarle, His Britannic Majesty’s ambassador in Paris, James Wolfe knew luxury: warmth, cleanliness, leisure, and more than adequate nourishment, eating for breakfast every morning fresh grapes from a convent garden, “the same as the King eats, and a great curiosity.” His health improved: his energy seemed boundless. “Monsieur Fesian, the dancing-master, assures me that I make a surprising progress, but that my time will be too short to possess, as he calls it, the minuet to any great perfection; however, he pretends to say that I shall dance not to be laughed at. I am on horseback every morning at break of day, and do presume that, with the advantage of long legs and thighs, I shall be able to sit a horse at a hand-gallop. Lastly, the fencing-master declares me to have a very quick wrist, and no inconsiderable lunge, for the reasons aforementioned… I wish I could send a piece of tapestry from the Gobelins, or a picture from the Palais Royal, instead of a letter.” He went to the theatre, became fluent in French, socialized, went sight-seeing, shopped, sending his mother two black velvet hoods and “a vestale for your neck, such as the Queen wears”, had his teeth filled, and observed the French: in the streets, in the salons, at the court of Versailles. On January 9th, 1753, he was presented to Louis XV, the Queen, the Dauphin, and, finally, the King’s mistress, the beautiful and fearless Jeanne Antoinette Poussin, Marquise de Pompadour. Philosopher, diplomat, political savant and patron of the arts, she had many enemies, but the intense young English soldier with whom she chatted in her boudoir, where she entertained visitors but offered a chair only to her royal lover, was not one of them. He recalled afterwards her intelligence, her wit and her courtesy, and that she was curling her hair during their conversation.

But despite the glitter and grace, life in Paris began to pall. He still hoped to be allowed to travel, perhaps to visit the French army in its summer encampment, but his request was denied and another officer was accorded the privilege. And then, peremptorily, he was ordered back to his regiment. He returned to England, wretchedly seasick as usual, and rejoined the 20th in Glasgow.

He found it in dire straits. “Officers ruined, impoverished, desperate, and without hopes of preferment; the widow of our late Major and her daughter in tears; an ensign struck speechless with the palsy, and another that falls down in the most violent convulsions. Some of our people spit blood, and others are begging to sell before they are quite undone, and my friend Ben will probably be in jail in a fortnight…. The ladies are cold to everything but a bagpipe— I wrong them. There is not one that does not melt at the sound of an estate. We march out of this dark and dismal country in August.”

He was beginning to wish he had stayed in Paris.

***

But it was a soldier’s life and he was a soldier’s soldier, committed to service. Younger officers came and went on their own career trajectories: he guided them, advised them, trained them, disciplined them, and, conscious of an increasing abruptness and austerity in himself, encouraged them to mingle in society, and go to balls and assemblies. “It softens their manners and makes ’em civil; and commonly I go along with them, to see how they conduct themselves. I am only afraid they shall fall in love and marry. Whenever I perceive the symptoms, or anybody else makes the discovery, we fall upon the delinquent without mercy until he grows out of conceit with his new passion…. My experience in these matters helps me to find out my neighbour’s weakness, and furnishes me with arms to oppose his folly.”

Sometimes he reflected darkly on the future, and was not reassured.

“I am eight-and-twenty years old, a lieutenant-colonel of foot, and I cannot say I am master of fifty pounds.”

His requests for promotion had been denied. He was too young for higher rank, they said, although he had seen other officers promoted, not on the basis of merit but out of political expediency. He felt old, jaded, bitter, forgotten.

He prayed for war.

War came.

***

The amphibious assault on Rochefort in the Charente estuary in September of 1757 was a million-pound fiasco involving sixteen ships of the line, frigates, fireships and bomb ketches, as well as ten line regiments, fifty horse, and gunners, a total of about 10,000 men. Intelligence had suggested the town contained a large arsenal of arms and ammunition and was only lightly guarded, and it was thought an ideal diversion to aid Hanover and Prussia, where a French army of 150,000 was preparing for attack.

Only two officers emerged from the resulting debacle with their reputations intact: Captain the Honourable Richard Howe of the 74-gun former French prize H.M.S. Magnanime, who had bombarded into submission the fortifications on the Île d’ Aix that commanded the approaches to Rochefort and La Rochelle; and the army’s quartermaster-general, James Wolfe, who after reconnoitring the area by boat had recognized the strategic necessity and recommended that the fort be destroyed.

Wolfe had been plucked from the obscurity of fly-fishing, shooting game birds without a licence, suppressing a riot by local weavers striking for higher pay, and other diversions of garrison life in Gloucestershire, on the recommendation of Sir John Mordaunt. General after general had declined the honour of leading the expedition, or had been vetoed by the King: the secretary of state, William Pitt, had eventually offered Mordaunt command. Wolfe was told nothing of the destination, nor were any other senior officers until they had been at sea for a week.

The troops had mustered on the Isle of Wight and waited for the transports. And waited. The weather turned against them and delayed embarkation. It was a bad beginning. Things got worse.

Mordaunt had been a brave and competent soldier, but he was sixty now, and ailing, and he had lost his nerve. He vacillated, unable to decide where or when or how to attack, issuing and countermanding orders, infuriating Vice-Admiral Sir Edward Hawke, who threatened to withdraw his ships if Mordaunt could not stop procrastinating; and, as Wolfe wrote to his father, “We lost the lucky moment in war, and were not able to recover it. It had been conducted so ill that I was ashamed to have been of the party. The public could not do better than to dismiss six or eight of us from the service. No zeal, no ardour, no care or concern for the good and honour of the country.”

After a court of inquiry in November, Mordaunt was brought before a court-martial on December 14th, charged with disobeying his orders. Given the fate of Vice-Admiral the Honourable John Byng, who had been executed by firing squad on the quarterdeck of H.M.S. Monarch in Portsmouth harbour in March for failing to defend Minorca, his acquittal was considered lenient. He was allowed to retire from the service.

Wolfe, who had given evidence at the court of inquiry and at Mordaunt’s court-martial, had refrained from any public criticism of him, but he plunged into depression and decided to resign his commission as quartermaster-general for Ireland, an office he had held only in name, hiding at his parents’ new house in Blackheath and writing to his mother, who had gone to Bath: “I can’t part with my other employment because I have nothing else to trust to, nor do I think it consistent with honour to sneak off in the middle of a war.” To Rickson he vented his shame and humiliation. “I own to you that there never was people collected together so unfit for the business… dilatory, ignorant, irresolute, and some grains of a very unmanly quality, and very unsoldier-like or unsailor-like.” And then, perhaps considering the repercussions if his comments as a prominent member of the expedition should become more widely known: “I have already been too imprudent; I have said too much. Therefore report nothing out of my letter, nor name my name as author of any one thing.”

He was thirty years old, angry, frustrated, alone. The future was a void.

***

There is a tide in the affairs of men/ which, taken at the flood, / leads on to fortune.

The tide turned.

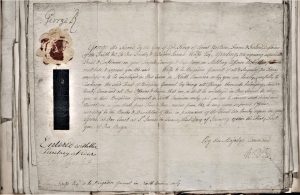

Wolfe’s commission as brigadier-general for Louisbourg

He had written of zeal and ardour. His own had not gone unnoticed. Vice-Admiral Hawke had spoken of his exemplary behaviour at Rochefort to Admiral Anson, who had mentioned it to the King; the Prince of Wales, summoning ‘Mister Wolfe’ to discuss the newly published Report of the General Officers appointed to inquire into the causes of the Failure of the Late Expedition to the Coasts of France, opined that had Wolfe’s proposals been adopted the mission would have been a success, and complimented him on the ‘high spirit of service’ and discipline in the 20th, the regiment on which Wolfe had lavished so much care and attention. A second battalion had been authorized, to be designated the 67th Foot. Wolfe was offered a full colonelcy.

There was more. By Christmas Day it was known in army circles that four colonels, all relatively young, had been chosen to launch a new North American offensive. Jeffrey Amherst, aide-de-camp to the venerable Field-Marshal Lord Ligonier, commander-in-chief of the forces since the Duke of Cumberland’s disgrace, had been commissioned major-general and would be in overall command. The others were John Forbes, another protégé of Ligonier’s, George Augustus, third Viscount Howe, brother of Captain Richard Howe of H.M.S. Magnanime and a charismatic soldier already serving in America; and the youngest, James Wolfe, who would be temporarily commissioned brigadier-general in North America and serve as second-in-command to Amherst.

Their objective was Cape Breton, an island in the Gulf of St. Lawrence between Newfoundland and Nova Scotia held by the French since 1713, and its fortress, Louisbourg. It had been beseiged in 1745 and had surrendered, and it had been returned to France under the terms of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle. It protected the rich fisheries of the St. Lawrence, and was a haven for the privateers who harassed the New England colonies.

Whoever held Louisbourg held the key to Canada. Whoever took Quebec and Montreal would hold North America.

***

Louisbourg surrendered on the 27th of July, 1758. Its fortifications had appeared impregnable, but it was vulnerable to sustained bombardment from the sea as well as fire from batteries overlooking the harbour, which had been hastily constructed and commanded by James Wolfe. He had been an integral part of the operation, seen everywhere, issuing orders and instructions in a display of physical courage and deeply personal leadership: instantly recognizable with his wings of auburn hair and shabby scarlet coat, without lace or insignia except for the aiguillette on his shoulder. The Highlanders, who had a particular fondness for him (or his Celtic hair, he thought), called him ‘the red corporal’ and passed the word when he was approaching. He learned to recognize the Gaelic, and to appreciate the nickname. “He was tall, and as straight as a rush,” one of them said, recalling him in 1828. “Oh, he was a noble fellow. And so kind and attentive to the men, that they would go through fire and water to serve him.” Lieutenant Thomas Bell, a marine, reported that he “built fresh batterys every day… and with his small corps came and took post within 200 yards of the town, while the engineers were still bouggering at 600 yards distance. He opened the trenches, called in the army, and pushed them within forty yards of the glacis and in short took the place without the assistance of any one regular fumbler. He has been general, soldier, and engineer. He commanded, fought and built batterys and I need not add has acquired all the glory of our expedition.”

He called them ‘brother soldiers’: they remembered him, sunburned and sweating, sitting amongst them, red hair tied back with a piece of cord, scribbling a message to Amherst “from the trenches at Daybreak, the 25th. We want platforms, artillery officers to take the direction, and ammunition. If these are sent early, we may batter in breach this afternoon…. Holland has opened a new boyau, has carried on about 140 or 150 yards and is now within 50 or 60 yards of the glacis…. You will be pleased to indulge me with six hours’ rest, that I may serve in the trenches at night.”

They breached the bastions. Heated shot had already destroyed L’Entrepreneur. The Royal Navy commanded by Admiral the Honourable Edward Boscawen had scattered the French warships which had been at anchor, cut out the Bienfaisant in the harbour and burned the Prudent; and, confronted with the prospect of point-blank broadsides and an assault by the fourteen battalions under Amherst’s command, the governor, Augustin de Boschenry de Drucour, capitulated and asked for terms. He and his garrison of 3,500 became prisoners of war and were transported to England. Amherst considered an attack on Quebec. Wolfe, never shy of speaking his mind, urged him forcefully to seize the moment. Boscawen demurred, announcing on August 3rd that he would not support the idea: the fogs and storms of summer in Cape Breton would usher in the equinoctial gales, and the St. Lawrence would freeze in the winter. There was only time to destroy the enemy’s fisheries in the Gulf.

They were a legitimate target. Twenty-six local chaloupes had sailed the week before laden with tons of dried cod for Quebec, where, the crew of a captured French sloop had said, “there was a great scarcity of provisions, and great distress.” And Wolfe was grieving for Howe, who had been among a thousand killed in an attack in the wilderness near Ticonderoga on July 6th by 3,000 French regulars and their native American allies under the command of Louis-Joseph, Marquis de Montcalm de Saint-Véran. Many of the dead had been scalped. The war had had its moments of chivalry, in the graceful exchange between Amherst and Mme Drucour of pineapples for champagne and fresh butter, but it had become a thing of unique horror, and the men who waged it would be stained by it.

They burned nets, boats, buildings and 30,000 pounds of dried cod. Privately, Wolfe thought the inhabitants of the Gaspé would starve; but it was war, and Quebec would starve also.

He sailed for home with Boscawen at the end of September, missing by days a letter from the War Office ordering him to remain in Nova Scotia. He wrote to Rickson from London.

“Our attempt to land where we did was rash and injudicious, our success was unexpected (by me) and undeserved. There was no prodigious measure of courage in the affair; an officer and thirty men would have made it impossible to get where we did. Our proceedings in other respects were as slow and tedious as this undertaking was ill-advised and desperate. We lost time at the siege, still more after the siege, and blundered from the beginning to the end of the campaign.

“… I have this day signified to Mr. Pitt that he may dispose of my slight carcase as he pleases. I am in a very bad condition both with the gravel and rheumatism, but I had much rather die than decline any kind of service that offers. If I followed my own taste, it would lead me into Germany. However, it is not our part to choose, but to obey.”

And to one of his captains: “It is my fortune to be cursed with American service.”

He was now a household name in Britain. The London Gazette, The London Magazine, The Gentleman’s Magazine, The Scots Magazine, were printing letters and eyewitness reports from men who had served at Louisbourg, extolling the extraordinary exploits of the young Brigadier James Wolfe.

In the middle of December the Prime Minister summoned him. If the past was prologue, James Wolfe’s entire life had been merely the prologue to Quebec.

***

Katherine Lowther

Events moved quickly, and not only in Wolfe’s professional life.

Her name was Katherine Lowther, and she was his parents’ “pretty neighbour” at Bath, whose sleep he had apologized for disturbing by his clattering departure one winter morning two years before. Her pedigree was impeccable: her father had been a governor of Barbados; one of her grandfathers was a baronet, her grandmother the daughter of a viscount; her sister was the Countess of Darlington. It was not the coup de foudre which had shattered Wolfe’s life in 1749 and he said he had “no thought of matrimony”, but there was clearly commitment; and he took his final leave of his parents by letter, claiming that he disliked the emotional business of parting. Henrietta Wolfe remained jealous and suspicious, and Lieutenant-General Edward Wolfe altered his will, leaving his considerable estate to his wife, with no provision for his son.

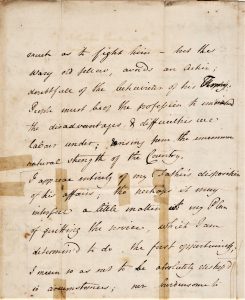

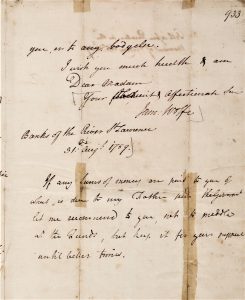

Wolfe learned of this in Louisbourg in May, following a rough passage in H.M.S. Neptune to New York, and from there to a fogbound Halifax, the harbour of which was still choked with ice. Edward Wolfe’s death in March had not been unexpected, as “I left him in so weakened a condition that it was not probable we should ever meet again”, but the financial blow was a heavy one, although he wrote to Henrietta from “the Banks of the St. Lawrence, 31st August 1759…. I approve entirely of my father’s disposition of his affairs, though perhaps it may interfere a little matter with my plan of quitting the service, which I am determined to do at the first opportunity— I mean so as not to be absolutely distressed in circumstances, nor burdensome to you or any one else.”

He had made his will aboard Neptune, leaving to Katherine the miniature she had given him, “to be set in jewels to the amount of five hundred guineas, and returned to her.”

Perhaps the future would always be only this: an endless repetition of the past. A flirtation with life, the certainty of death, an evanescent dream.

He disposed, generously, of his other assets, and his aides witnessed his signature. There was nothing else, nothing more. The rest, even she, was illusion.

***

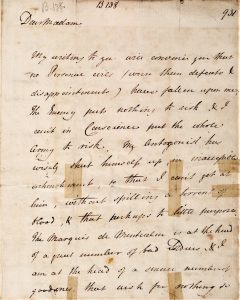

Wolfe’s last letter to his mother, from the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Collection, University of Toronto

He burned his personal journal for August, with its bitter catalogue of affront, resentment, suspicion, foreboding and depression, and its accounts of “a sad episode of dysentery”, not now uncommon in an army encamped in extreme heat and humidity, and increasingly severe bouts of renal colic. He had asked for something to ease the pain, fearing that events would slip beyond his control, and that he would be unable to prosecute this final attack on a tenacious and unaccommodating enemy.

“My antagonist has wisely shut himself up in inaccessible entrenchments, so that I cannot get at him without spilling a torrent of blood, and that perhaps to little purpose. The Marquis de Montcalm is at the head of a great number of bad soldiers, and I am at the head of a small number of good ones, that wish for nothing so much as to fight him; but the wary old fellow avoids an action, doubtful of the behaviour of his army. People must be of the profession to understand the disadvantages and difficulties we labour under, arising from the uncommon natural strength of the country.”

Rumours of his illness had disconcerted men already unnerved by a summer of skirmishes and scalpings, and sniping by disaffected habitants bearing arms and grudges against the British.

“The French did not attempt to interrupt our march. Some of the savages came down to murder such of the wounded as could not be brought off, and to scalp the dead, as their custom is…. Scarce a night passes when they are not close upon our posts, watching an opportunity to surprise and murder. There is very little quarter given on either side.”

It revolted him. His orders of the 24th of July read: “The General strictly forbids the inhuman practice of scalping, except where the enemy are Indians, or Canadians dressed as Indians,” but a subsequent order posted a bounty of five guineas for an aboriginal scalp. The Canadians were offering a similar reward for a British scalp, and after a Captain Alexander Montgomery of the 43rd Foot found his brother’s body “cruelly mutilated by the savages” he had reciprocated in a manner they understood: he and his men had murdered and scalped a priest and twenty of his congregation when they had refused to disarm in St. Joachim on the 23rd of August.

In every man of every race the creed of the frontier, the inner savage, was asserting itself.

“No churches, houses or buildings of any kind are to be burned or destroyed without orders. The persons that remain in their habitations, their women and children are to be treated with humanity. If any violence is offered to a woman, the offender shall be punished with death. If any persons are detected robbing the tents of officers or soldiers they will be, if convicted, certainly executed. The commanders of regiments are to be answerable that no rum, or spirits of any kind, be sold in or near the camp.”

But it was the enemy within he hated: not Montcalm, not the Canadians, not the Iroquois Confederacy, but a confederacy of his own brigadiers, sworn to subvert, discredit and undermine his authority. His right to choose his own staff officers had been a condition of his acceptance of command, and he had thought he knew them: his aides, Captains Hervey Smith and Thomas Bell, remained loyal and protective of him. An Irish major named Isaac Barré was adjutant-general: he had not yet betrayed Wolfe’s trust. The others were his quartermaster-general Lieutenant-Colonel Guy Carleton, an Irish veteran of Flanders whose commission for Louisbourg the King had refused to sign because Carleton had insulted the Hanoverians: even Carleton, a friend, had offended Wolfe by his “abominable behaviour”; the Honourable Robert Monckton, brigadier-general commanding the first battalion, who had been lieutenant-governor of Nova Scotia and had overseen operations in the Bay of Fundy after Louisbourg; and the Honourable James Murray, brigadier-general commanding the third battalion, a touchy Scot whose brother was a known Jacobite, and who had served in Flanders and at Rochefort and Louisbourg. He was increasingly influenced by Colonel the Honourable George Townshend, honorary brigadier-general in command of the second battalion. Townshend had been Pitt’s choice, not Wolfe’s. He had fought in Flanders and at Culloden, been aide-de-camp to Cumberland and then to George II, and was called by Horace Walpole “proud, sullen and contemptuous”. He was also a maliciously talented cartoonist, and had satirized Cumberland to the detriment of his own career. He now found in Wolfe both subject and target, and was circulating with impunity his caricatures of ‘Our General’, hinting that Wolfe’s judgment was clouded by opium and that his refusal to disclose his plan of attack was indecision or, at worst, paranoia.

Wolfe at Quebec, portrayed, remarkably without malice, by George Townshend

Wolfe was, by his own admission, “so ill and so weak that I begged the General Officers to consult together for the public utility and advantage; and to consider of the best method of attacking the enemy.” He offered them what he called “a choice of difficulties”. They rejected all three options and mooted one of their own, Townshend claiming afterwards that Wolfe had never had any intention of forcing a pitched battle at Quebec.

For a man who was bluffing or indecisive, or too ill or too drugged to function, his mind remained exceptionally focused, detailing the siting and calibre of artillery, and designating specific ships, batteries, and signals; collating information from every source including deserters, whom he questioned himself; conducting solo reconnaissances on foot or by boat; noting the dispersal of Montcalm’s forces, the Duc de Lévis somewhere between Quebec and Montreal with an army of 4,000 chosen men, Colonel Louis-Antoine de Bougainville at Cap Rouge with another 3,000 regulars, militia and aboriginals; reading the reports of shortages and damage within the city; considering the logistics: the immutable, the inalienable, the impossible. He knew every officer and had trained personally many of the men: the combined forces were now a weapon poised to strike when the time and the tide and the peculiarities of the river and the phase of the moon dictated. He had seen the place in early July, and had conferred with the navy’s navigators and cartographers, among them James Cook. The time was now.

Those commanders he trusted he briefed in full, including the navy, with which close co-operation was vital. He issued his final orders on the afternoon of September 12th, from aboard H.M.S. Sutherland.

“The enemy’s force is now divided; great scarcity of provisions is in their camp, and universal discontent among the Canadians. The second officer is gone to Montreal or St. John’s, which gives reason to think that General Amherst is advancing into the colony. A vigorous blow struck by the army at this juncture may determine the fate of Canada. Our troops below are in readiness to join us; all the light artillery and tools are embarked at Point Levi, and the troops will land where the French seem least to expect it.

“The first body that gets on shore is to march directly to the enemy, and drive them from any little post they may occupy. The officers must be careful that the succeeding bodies do not by any mistake fire upon those who go before them. The battalions must form on the upper ground with expedition, and be ready to charge whatever presents itself. When the artillery and troops are landed, a corps will be left to secure the landing-place, while the rest march on, and endeavour to bring the French and Canadians to a battle. The officers and men will remember what their country expects from them, and what a determined body of soldiers, inured to war, is capable of doing against five weak French battalions mingled with disorderly peasantry. The soldiers must be attentive and obedient to their officers, and the officers resolute in the execution of their duty.”

At 8 p.m., as the troops were climbing down into Sutherland’s boats, he received a letter signed by all three brigadiers, demanding further clarification. Security was necessary, they conceded, but they had not been taken fully into the General’s confidence, and their orders were not specific.

He wrote to Monckton: “My reason for desiring the honour of your company with me to Gorham’s post yesterday was to show you, as well as the distance would permit, the situation of the enemy, and the place where I meant they should be attacked. The place is called the Foulon, distant upon two miles or two and a half from Quebec… as several Ships of War are to fall down with troops Mr. Holmes will be able to station them properly after he has seen the place…. The officers who are appointed to conduct the divisions of boats have been strictly enjoined to keep as much order and to act as silently as the nature of the service will admit of. It is not usual to point out in the public orders the direct spot of our attack, nor for any inferior officers not charged with a particular duty to ask instruction upon that point. I had the honour to inform you today that it is my duty to attack the French army. To the best of my knowledge and ability I have fixed upon that spot where we can act with the most force and are the most likely to succeed. If I am mistaken, I am sorry and must be answerable to his Majesty and the public for the consequences.”

To Townshend, controlling his dislike, he wrote: “Brigadier-General Monckton is charged with the first landing and attack at the Foulon, if he succeeds you will be pleased to give directions that the troops afloat be set on shore with the utmost expedition, as they are under your command, and when 3,600 men now in the fleet are landed I have no manner of doubt but that we are able to fight and beat the French army, in which I know you will give your best assistance.”

To Murray, who was under Monckton’s command, he wrote nothing.

At 2 a.m., time and tide ebbing, Sutherland’s barge took the lead.

***

On the right of the line to the edge of the cliffs, with Wolfe in personal command, the 35th, the Louisbourg Grenadiers, the 28th, the 43rd. In the centre under Monckton: Lascelles’, the 47th, Scots who had fought Scots at Prestonpans and Culloden. On the left, Murray with the 78th, the Fraser Highlanders, born, perhaps of a conversation one evening in Inverness between Wolfe and Simon Fraser, whose father, the Jacobite Lord Lovat, had been beheaded for treason in 1747. Fraser had been out with his clan for the Pretender in the ’45 and had been pardoned in 1750. Wolfe had suggested he raise a regiment for the King, and the Frasers were here now, bristling with the weapons the Disarming Act of 1746 still forbade civilians to carry in Scotland. They were, he acknowledged, among the finest soldiers he had ever known. Beside them, Anstruther’s; and in the second line, where Townshend could do the least damage, the 15th and two battalions of the 60th. In reserve, Lieutenant-Colonel Ralph Burton’s 48th in eight subdivisions; and at the rear Colonel the Honourable William Howe, another friend of Wolfe’s, with the rangers and light infantry.

The French colours surrendered at Louisbourg had been paraded in London, and put on display in St. Paul’s Cathedral. He did not want to see these six-foot standards, the King’s colours and these regiments’, so dishonoured in Paris.

Daybreak: just after 5 a.m. The rain fell. They waited, unmoving. The ‘plains’ were fairly level, but patched with cornfields and studded with undergrowth and coppices that afforded cover to native and Canadian marksmen. The French picquets, running, had reached Quebec with intelligence that the entire British army was established on the heights to the westward, on, Montcalm noted, “the weakest side of this miserable garrison,” and had by their presence thrown down a psychological gauntlet no soldier of honour could ignore.

By 7 a.m., in showery rain, the French were seen coming out, one eyewitness reported, “like bees from a hive.” Sniping by Canadian irregulars and their aboriginal allies intensified. The French opened fire with artillery, and the hailstorm of lead from the Canadians became “very galling”. Rather than sacrifice men’s lives prematurely, Wolfe ordered the infantry to lie down briefly in their ranks. The French formed three columns, some 7,500 men, and at about 10 a.m. began to advance. The thin red lines waited.

Apprêtez vos armes…. En joue…. Feu!

From his position on the right, on slightly rising ground, Wolfe observed. A soldier wrote later, “I shall never forget his look. He was surveying the enemy with a countenance radiant and joyful beyond description.”

A bullet tore the tendons of his right wrist. He tied it up with his handkerchief: it seemed to cause no pain. The fire was very hot now from the sharpshooters: he could handle a fusil as well as any sergeant and he tore the cartridge with his teeth and spat out the fragment, and waited: every musket in the line was double-shotted on his orders. Amongst the French there were shouts: obscenities, jeers, encouragement, shouts of Vive le Roi! and Marquez bien les officiers! And marked they were, in the oblique fire from the Royal Roussillon, the Compagnies Franches de la Marine, the battalions of La Sarre, Languedoc, Béarn, Guyenne: Monckton shot in the chest, his left lung collapsing, Carleton sustaining head wounds, Barré’s nose and left cheekbone smashed by a musket ball, his left eye blinded.

They took it, standing impassively with shouldered arms. One hundred and forty yards; one hundred and twenty. The French had four or five field guns: they had hauled only two up the cliffs. A hundred. Hold your fire. Eighty. Sixty. Hold your fire, damn you. At forty yards, on the command, they opened fire: a single volley in unison, which had the effect of a cannonade. When the smoke cleared the plain was littered with greyish-white uniforms, stained scarlet: the dead, the dying, the mutilated. They fired another five volleys. It was 10:15 a.m. and the sun had come out, glinting on bayonets. From farther along the line there was a hiss of drawn steel as the Highlanders unsheathed their broadswords.

A quarter-inch of metal, a bullet or shrapnel from an exploding shell, hit Wolfe in the groin: they were under heavy fire from the front and flank, and he was too conspicuous a target to ignore. He waved his hat, signalling that the whole line should advance; and then two bullets pierced his left breast, and he staggered and almost fell. He was caught, supported. “Hold me up,” he said, “don’t let my brave fellows see me fall.” He leaned on Captain Ralph Corry of the 28th, and then there were others: Lieutenant Henry Browne of the Louisbourg Grenadiers, a volunteer named James Henderson, another officer: blue coat, red facings. Artillery. He tried to help them, but his strength and his vision were failing: he collapsed, and they carried him through the smoke another hundred yards to the rear. Henderson held him upright while Browne tore at his waistcoat, and saw that his shirt was soaked with blood. He attempted to dress the wound, but the haemorrhage could not be staunched. He asked if Wolfe wanted a surgeon.

“No need,” he said, “it’s all over with me.”

Some one else, a grenadier, was shouting.

“They run! See how they run!”

He stirred, rousing himself, they said afterwards, like a man from heavy sleep. “Who run?” he said, and the grenadier, shocked by what he was witnessing, answered, “The enemy, sir. Egad, they give way everywhere.”

One more order, and then there would be peace. He said, “Take a message to Colonel Burton. Tell him to take Webb’s with all speed to Charles River, to cut them off before they reach the bridge.”

And then to Browne, whose arms were around him, “Lay me down. I am suffocating.”

Browne, crying openly, laid him gently on the ground, and cradled him as he died.

***

He had been greatly loved, far more than he had known. Browne wrote to his father: “Even the soldiers dropped tears, who were in the minute before driving their bayonets through the French. I can’t compare it to anything better, than a family in tears and sorrow which had just lost their father, their friend, and their whole dependence.” Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander Murray of the Louisbourg Grenadiers wrote to his wife, “His death has given me more affliction than anything I have met with, for I loved him with a sincere and friendly affection.”

His body was carried from the field wrapped, it was said, in a plaid offered by a wounded Highlander, and brought aboard the 28-gun frigate H.M.S. Lowestoft at 11 a.m. It was embalmed, and eventually placed in a stone sarcophagus taken from the convent of the Ursulines, which had been heavily damaged by bombardments from the batteries at Pointe aux Pères: Montcalm was buried there at 8 o’clock on the evening of the 14th in an enlarged shell hole in the floor. Quebec capitulated on September 18th. Montreal fell a year later.

News of the victory reached England on October 27th and the country went wild with bonfires and celebrations, although friends and neighbours in Blackheath refused to illuminate their houses out of respect for James’s memory, and his mother’s very real grief.

Wolfe, sculpture by Joseph Wilton, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Wolfe’s body, brought home aboard the 84-gun H.M.S. Royal William, arrived at Spithead at 7 a.m. on the morning of Saturday, November 17th. The raucous port he had called “this infernal den” was hushed as Royal William’s barge, escorted by others and to the sound of tolling bells and muffled drums, conveyed the sarcophagus to Portsmouth Point. Now transferred to an oak coffin and accompanied by Captains Thomas Bell and William De Laune, it was placed in a hearse and driven to Blackheath. It had been discovered on opening the sarcophagus that the face had decomposed too much to allow a death mask to be made: the sculptor Joseph Wilton modelled his commemorative marble bust on a servant thought to resemble Wolfe. He was advised by Richard, second Baron Edgcumbe, a draughtsman and patron of the arts who had known Wolfe and was able to recreate the beaky, angular features to an almost forensic degree.

Wolfe’s coffin, covered with a pall of black velvet and heaped with laurels, lay in state at his mother’s house the night before a private funeral on November 20th at the church of St. Alfege in Greenwich. There were five mourners, all male. Henrietta Wolfe remained prostrate with grief, and did not attend.

She petitioned the government unsuccessfully for Wolfe’s pay to be increased to parity with Amherst’s, and “for a pension to enable me to fulfil the generous and kind intentions of my dear lost son”, which she said she could not otherwise honour “without distressing myself to the highest degree.” She did, however, pay the jeweller Philip Hardle £525, and returned the miniature, set with diamonds, to Katherine Lowther as Wolfe had requested. Katherine wrote to her, but dared not call on her. “Your displeasure at your noble son’s partiality to one who is only too conscious of her own unworthiness has cost her many a pang. But you cannot without cruelty still attribute to me any coldness in his parting, for, madam, I always felt and express’d for you both reverence and affection, and desir’d you were ever first to be considered.”

They never met again.

Henrietta Wolfe died on the 26th of September, 1764, and was interred between her son and her husband in the family vault in the church of St. Alfege. Katherine Lowther married Vice-Admiral Harry Powlett, later the sixth Duke of Bolton, on April 8th, 1765. Wolfe’s letters to her and those she wrote to him at Quebec, which arrived too late and were returned to her unopened, have not survived. She died in 1809.

In England, he is all but forgotten. In Canada, the tides of political correctness alternately burnish and tarnish his reputation. The vast, untamed country of which he said “every man is a soldier” is now dedicated to peacekeeping: bears and beavers still roam the wilderness; and the snow, falling early and lingering long, still, in the true north, covers the ground for eight months of the year.